Harmony in urban chaos: Kerala’s commission lights the path

Shimla, Dec 28

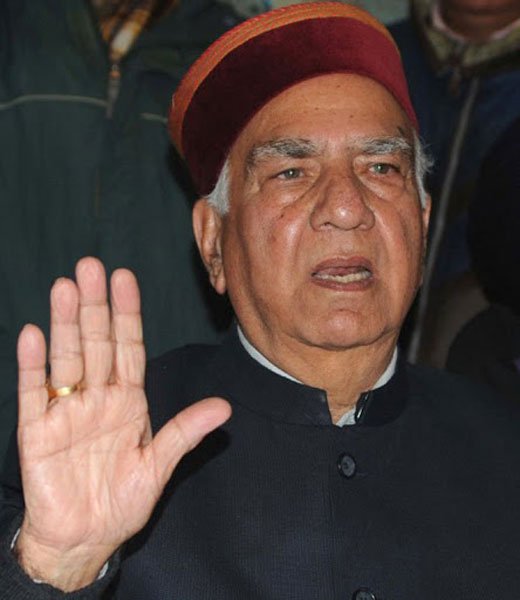

In a significant move, former Deputy Mayor of Shimla Tikender Panwar has taken on a new role as a member of the Kerala State Urban Policy Commission. In an exclusive interview with Himachal Scape, Panwar sheds light on the uniqueness of the commission, delving into the challenges it faces in navigating the intricate landscape of urban development and addressing the crucial urban-rural divide within policy frameworks.

Originating from the visionary efforts of the first state government in the Nation, Kerala, the concept of the Urban Commission has now found resonance. As HimachaScape team embarks on this interview, Panwar unfolds the narrative of a commission poised to revolutionize urban policies, with a particular focus on relevance of such an initiative for Himachal Pradesh.

What does the Commission aim to do?

Answer: The commission aims to replicate the model founded by former Prime Minister Rajeev Gandhi in 1985. Gandhi envisioned managing migration from rural to urban areas and vice versa to regulate the population and allocate resources in civic bodies. Although the National Urban Commission was founded in 1985, the subsequent liberalization path led by the Congress, UPA government, and other successive governments of NDA couldn’t continue the basic provisions. The Commission will have a holistic approach towards the urbanization processes and try to capture them and make an objective assessment towards sustainable, nature based and inclusive alternatives.

Why an Urban Commission is necessary?

Answer: Post independent India has witnessed two stark periods of development in the urban spectrum. The foremost one was the famous Nehruvian period that lasted for almost three decades and started dwindling in the late 80s. During this period around 150 new towns were built and around 450 merged. The characteristic feature of this period was a centralized planning mechanism laying emphasis on master plans/ development plans. However, this process also failed miserably as it was drawn by the core idea of pushing millions of people from rural to urban with manufacturing being the driving force. Manufacturing did not remain the central pivot of driving migration to the cities as it fell miserably and new areas were opened up. The cities still drew millions into its fold with the informal sector taking the centre stage and the urban plans failing miserably.

Post 90s period is the one where abject privatization of the cities began and global cities were the image on which the development process was built. The master plans were handed over to large parastatals and big consultancy firms were hired to draw such plans. These companies gave away the concept of social housing, public health, education and real estate was supposedly to be the core element of this hypothesis. Cities were made competitive and termed as ‘engines of growth’, not spaces of enlightenment, future of dreams, habitat, etc. Instead of a whole city approach, project oriented approach was the guiding principle and thus we have the mission mode of development, JNNURM, and smart city mission were the buzz words. We know the reality. All of this failed miserably and now has come to a dead end.

Cities are screaming for some of the basic utilities. Air pollution is a major issue, traffic snarls are almost universal, solid and liquid waste management is across the spectrum, affordable housing is nowhere in the vicinity and all of this has led to highly unequal cities not worth living for the large majority of our population.

Why did urban interventions not help in addressing the basic urban challenges?

Answer: It is in this regard that the urban commission formed in 1985 has to be revisited and relooked. Piecemeal approaches won’t help and neither are they making any breakthrough. Hence an urban commission is required both at the national level and state levels to understand some of the interesting objective patterns of urbanization. Migration being one of them. Settlement being another one, information technology being one of the enablers but also disablers. A holistic understanding of the process is required and must be developed. In this light the Kerala Urban Commission formation must be seen.

The State of Kerala has adopted this urban policy commission initiative after a gap of 38 years. The commission’s mandate, is led by Chairman Dr. M. Sathishkmar and Co-Chairman Advocate M. Anil Kumar and Dr. E. Narayan, includes various members such as Dr. Janaki Nair, Krishanadass, Dr. K. S. James, V. Suresh, Dr. Ashok Kumar, Dr. Y. V. N. Krishnamurthy, and Tikender Singh Panwar, former Mayor of Shimla.

What is the period of this commission?

Answer: The commission’s 12-month mandate aims to address the challenges of urbanization, particularly in the context of Kerala’s 47.71% urbanized population, though the NITI Ayog has estimated that currently 90% of Kerala is urban. Panwar emphasized that the commission’s approach should serve as a blueprint for future urban development.

Other states should learn from the Urban Commission, as regulatory bodies under Urban Development struggle with migration challenges without understanding geological and topographic realities. Panwar stressed that the commission is crucial in the face of natural disasters and climate changes, as highlighted by the IPCC report.

Around 200 cities worldwide act as magnet cities, attracting rapid migration for security, food, employment, and commercial ventures. Drawing from my experience as City Deputy Mayor, that urban policies are often neglected by national and federal governments, leading to a mismatch in policy implementation.

What could be its relevance for a state like Himachal Pradesh?

Answer: The commission’s relevance in Himachal Pradesh, with a migration rate of around 12% (2011 census), was questioned. I suggest that a re-evaluation of the migration rate is necessary. The complexity of urban concepts in Himachal, where small urban centers are modernizing, needs to be studied. Thereby I propose a “settlement commission” for Himachal Pradesh to address urbanization challenges specific to the hill state.

Panwar emphasized the need for a macro-level settlement commission to plan the future of urbanization in Himachal Pradesh. He argued that existing planning bodies, such as MCs, Village Panchayats, and TCP, are insufficient to address settlement patterns, infrastructure planning, and the unique architecture required for mountainous regions.

He suggested learning from Kerala’s experience and improvising a Himachal-specific plan. Panwar stressed the importance of community collaboration in envisioning a new model for urban development in Himachal Pradesh, addressing challenges in infrastructure, tunnels, and NH expansion.

In conclusion, Panwar emphasized that the Urban Commission’s role is crucial in managing changing dynamics within associated sectors, shaping Kerala as an equitably resilient society in the face of challenges like housing, real estate, motility patterns, education, skill markets, climate events, waste management, physical and mental health, aging, and progress towards a digital society.

The HimachalScape Bureau comprises seasoned journalists from Himachal Pradesh with over 25 years of experience in leading media conglomerates such as The Times of India and United News of India. Known for their in-depth regional insights, the team brings credible, research-driven, and balanced reportage on Himachal’s socio-political and developmental landscape.